_____________________________

In David’s words

_____________________________

When the final exuberant chords of Dvořák’s Quintet reverberated in the hall at Menlo-Atherton, the twelfth season of Music@Menlo had seemed to go by so quickly that we couldn’t believe it was really over. When one is as busy as Wu Han and I are during the Festival, days blur from one to the next, the sense of time passing is suspended, and suddenly it’s all over. In some ways, it seems like yesterday that we greeted the 44 young musicians attending the Chamber Music Institute, and yet, it also seems like a year ago that they bravely launched into their first assignments.

As is always our practice at Music@Menlo, we delved deeply into music through a particular lens, which was, this summer, the life and world of the great Czech composer Antonín Dvořák. The ways in which we explore music at the Festival always provide the richest and most meaningful contexts in which to experience the works of great composers, and for Dvořák, who was so widely regarded and well-traveled during his life, we decided to focus this lens very widely, to include the composers and cultures of Dvořák’s neighbors in Hungary, Romania, Germany and Austria. Included among those composers were Dvořák’s musical ancestors, contemporaries and descendants, all of who could be connected to Dvořák. Among them were: Johannes Brahms, Dvořák’s mentor and advocate from Vienna; Franz Schubert, also from Vienna, whose music inspired many of Dvořák’s compositions; Beethoven, who set a lofty example for Dvořák of what it meant to be a true artist; Leoš Janáček, the great 20th century descendant of Dvořák’s tradition who translated the Romantic era’s passion into modern musical language; and Erwin Schulhoff, a Czech composer of enormous talent and promise, encouraged to pursue a career as a young boy by Dvořák himself, who needlessly perished in a Nazi concentration camp in 1942.

Without exaggeration, hardly a moment passes during these three weeks that is not in some way very special, very memorable, and very important to the life and character of the festival.

Some of my favorite recurring festival moments include: the daily morning meeting of all the Chamber Music Institute students and faculty, during which the day’s events are described and anticipated in exciting detail; sitting in the recording booth with our brilliant producer Da-Hong Seetoo as he listens with phenomenal concentration to a performance being captured for Music@Menlo Live, our in-house recording label; lunch with students, faculty, performers and friends on the beautiful campus of Menlo School, our host and partner; a concert in Menlo School’s Stent Family Hall, one of the most beautiful rooms imaginable in which to hear chamber music; attending a Café Conversation during which our visiting performers often unveil and share with us a wide selection of their projects, passions and experiences; watching both Young Performers and International Performers rise to new heights of poise, precision and artistry in performances; welcoming an exciting selection of artists every summer who are making their Music@Menlo debuts, and seeing our audience delight in newly-discovered talent and festival friends; and the list goes on and on.

Our Institute, which had its beginnings from the Festival’s very first year, has grown to serve an ever-wider range of students from the Bay Area and all over the world. We made a great effort this year to find ways to house students from afar, and this has opened up the possibility of bringing literally the best young musicians the world has to offer right into our mix, benefitting not only our voracious listeners, but the top young local talent, whose experience and standards are raised as they make music with new colleagues truly on their level. In addition, we’ve grown and developed our Chamber Music Institute faculty, and assigned each Institute component a director who oversees the activities of all the students. We now not only can say that we are offering young musicians an incomparable experience – which has always been the case – but also that we are increasingly able to make the Music@Menlo experience practical and affordable for the most deserving and eager young musicians of today.

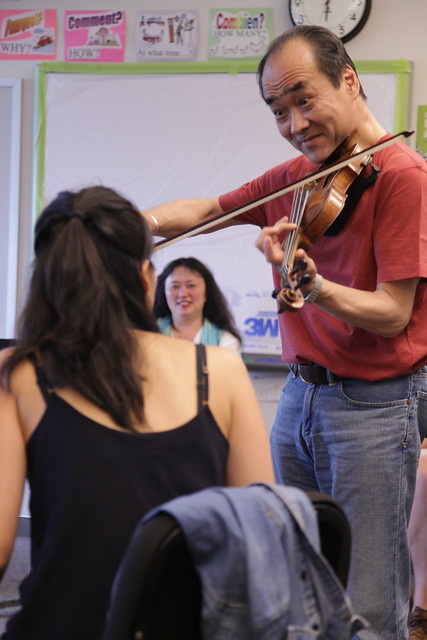

The Chamber Music Institute programs provide both no-cost performances to our community and invaluable chances for the young chamber musicians of future to play music and to host concerts in a thoroughly professional way. The daily coachings, the many master classes, all that the students absorb through attending the main-stage concerts and other performances, plus the Encounters and Café Conversations, all add up to an incomparable educational experience.

The impact of Music@Menlo on these young musicians is no better evidenced than at the Institute’s concluding concerts. The meticulous and passionate performances, the cheering of the packed house, and the many tears and hugs, onstage and off, make us as proud to be a part of this program as anything we do. A look at the following collection of photos can only begin to provide a true picture of what the Music@Menlo Chamber Music Institute is capable of providing to the deserving young musicians who represent the future of the art.

CMI coaches Dmitri Atapine, Hyeyeon Park, Gloria Chien, Sunmi Chang, Sean Lee, Nicolas Dautricourt

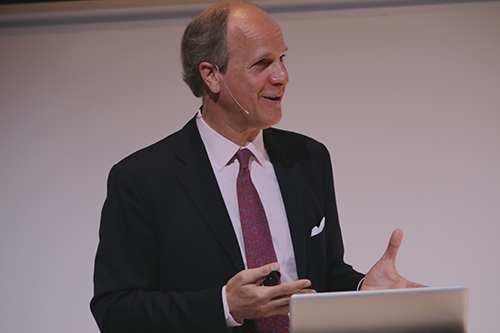

The 2014 festival began as most of our festivals have, with an initial Encounter that provides an overview of the festival and an in-depth look at the subject at hand. Perfectly suited for that mission was musicologist David Beveridge, a Dvořák expert, who made the journey all the way from Prague (where he lives and where we first met) to give us background and context on Dvořák and his world. David traced the incredible line of Dvořák’s career, from the son of simple butcher in a small Bohemian village to a composer of world renown. Included in the Encounter was a thorough geography lesson (something we can all use when talking about Middle Europe) and a fascinating examination of Dvořák’s compositional techniques, with musical examples provided by violinists Erin Keefe and Kristin Lee, violist Paul Neubauer, cellist Dmitri Atapine and bassist Scott Pingel.

Each Music@Menlo festival is anchored by a series of main concert programs that outline the festival’s theme. During our first festival in 2003, there were five of them, but that number has swelled on occasion to eight, which was the case this year. The eight programs, most of which were performed twice, were buttressed by many other events, among them the four Carte Blanche concerts and four Encounters, making the Festival a more-or-less wall-to-wall musical experience over three weeks.

“Around Dvořák” traced Dvořák’s life not only from the perspective of his own music but also that of his neighbors past, present and future. The first program, “Dvořák in Context” began with music by Mozart, one of Dvořák’s most inspiring predecessors from nearby Vienna, and concluded with music by a powerful descendant of Dvořák’s folkloric tradition, Béla Bartók. In Mozart’s Serenata Notturna, Wu Han made her Festival debut as timpanist, and a crackerjack ensemble composed of the Escher and Danish Quartets, plus individuals, gave a definitive performance of Bartók’s Divertimento.

Our second main-stage concert program, “Viennese Roots”, paid tribute to the effect of the great classical composers on Dvořák, whose expert craftsmanship gave structure and integrity to his passionate, nationalistic and folk-inspired works. Included on the program were two works of Schubert (about whom Dvořák wrote a learned article), his A-flat Impromptu performed with depth and mastery by Gilbert Kalish, and his flashy Rondo Brilliant for violin and piano, played with lyricism and panache by violinist Sean Lee and pianist Gloria Chien. The program opened with a sparkling trio by Haydn, which gave me chance to sneak on stage with Gloria and the marvelous violinist Kristin Lee, with whom I had the pleasure to play many concerts last season on tour with the Chamber Music Society, all across America, in Germany at the Dresden Festival, and on the CMS cruise in June from Venice to Dubrovnik.

Interspersed with our main concert programs and Encounters is another concert series called Carte Blanche, in which Wu Han and I invite extraordinary performers to design and perform programs of their own invention. This series, inaugurated in the festival’s second season, has had an amazing history, and this year’s offerings lived up to the series’ high standard of creativity and excitement. The first program of this year’s Carte Blanche series was performed by the Escher Quartet, simply one of the finest string quartets of now or any age, and they used both their incomparable virtuosity and impeccable traditional string playing style to render, in a single evening, all four quartets by Alexander von Zemlinsky. I daresay that, without having played these quartets myself, it seems to be feat of technique, concentration and stamina that far outweighs playing Bartók’s six quartets in one concert (something I am well-qualified to talk about). The Escher Quartet astounded the over-sold hall with as thrilling a quartet performance as I have heard anywhere, and their two-hour and forty-five minute concert was rewarded with cheers and a hearty meal (in the Music@Menlo tradition).

The main stage concerts continued with a program dedicated to the patronage of the seventh Prince Lobkowicz, Josef Franz Maximilian, a Bohemian nobleman who became the stand-out arts supporter of his family through his commissions and dedications from Haydn and Beethoven. A great lover of chamber music, especially string quartets, this prince kept a house orchestra from which could be formed smaller ensembles, and he enjoyed music in his many castles and palaces, from downtown Vienna to the idyllic Bohemian countryside.

The focus on the Lobkowicz family’s contribution to chamber music was heightened by the presence of today’s heir to the Lobkowicz properties, possession and legacy, William Lobkowicz, who was accompanied on his visit by his wife and three children.

William shared the incredible history of his family during an Encounter, and, in his honor, we resurrected a string quartet composed by the seventh prince’s house composer and orchestra leader, the Czech violinist Antonin Vranicky. William and Sandra listened from the side of the stage, and our quartet, formed with violinist Sean Lee, International Performers Becky Anderson and Cong Wu, and me on cello, was given official permission, upon request and on the spot, to call itself the New Lobkowicz Quartet (neither I nor many of my friends could quite believe I was back in a string quartet so soon – much less forming a new one!).

The main-stage concert program that honored the Lobkowicz family was composed entirely of works commissioned by the Seventh Prince: Haydn’s Quartet Op. 77 No. 2, and by Beethoven, the string quartets Op. 18 No. 1 and Op. 74,“Harp”, plus the song cycle “An die Ferne Geliebte”. Performing for us were Gilbert Kalish and the compelling baritone Randall Scarlata, and the popular Danish String Quartet, justifiably renowned both for the depth of their performances and the wildness of their hair.

The second concert in the Carte Blanche series was something of a double Carte Blanche, as the legendary Brazilian piano virtuoso Arnaldo Cohen has long been admired by Wu Han, who saw this summer’s programming line up with Arnaldo’s specialties, making it the perfect season to introduce this great pianist to the Menlo community in a single recital. His adventurous program paid tribute to the festival’s theme at every turn, traversing Bach-Busoni, Handel-Brahms, Liszt and Chopin, all delivered with apparent ease in show-stopping style, and all before lunch at that. Our audience warmly welcomed a completely new artist, and we have been asked again and again when he will return.

As we had focused on Beethoven so thoroughly through the Lobkowicz concert program, we decided to detour further in Beethoven’s world in concert program four, titled “Beethoven’s Friends”, by performing his music in the company of music by his famous friends and colleagues. Moreover, Anton Reicha was of Czech descent, and Johann Nepomuk Hummel was born in Hungary, so they were certainly well-qualified for Around Dvořák status. Their music was a discovery for many in our already-well-educated audience, which enjoyed these performances featuring both piano and winds.

Our third Carte Blanche concert was put in the hands of the estimable violinist Yura Lee, who cooked up (she’s a great cook as well so that’s apt to say) a program that one is likely going to hear nowhere else unless it’s Yura and her pianist Dina Vainshtein playing. Their program whole-heartedly served our season theme, ranging from the extraordinary Impressions d’enfance (Impressions of Childhood) by Georges Enescu, to Bartók’s essential Sonata no. 1 for violin and piano, with Dvořák, Suk and Hubay thrown in between. Yura played with her signature intensity and magical technical accuracy, and all left the hall amazed at both the music and performers.

In Concert Program five, titled “American Visions”, we followed Dvořák all the way to America, where he spent the years 1892-95 heading the National Conservatory in New York City. To document his experience in and effect on American musical culture, we created a sequence of music that told something of a story. Beginning with a rousing performance by Gilles Vonsattel of Gottschalk’s The Union, a medley of American popular songs coupled with ingenious, parlor-trick sound effects, the jovial piece became the perfect setup for Dvořák’s cheerful and quintessentially American-sounding Sonatina in G Major for violin and piano, composed during his stay, and performed for us by Wu Han and violinist Arnaud Sussmann.

The happy mood Dvořák created was then carried on by the first song in a set by the American maverick Charles Ives, and as Randall Scarlata and Gilbert Kalish moved from song to song, the music of Ives became more and more mystical and unsettling. This was exactly what we had hoped for, as we needed to set the mood for us all to experience the phenomenal American Songbook II: A Journey beyond Time, by contemporary legend George Crumb.

Joining us for the Crumb were Gilbert Kalish (without a doubt, the leading interpreter of Crumb’s music), Randall Scarlata, and percussionists Ayano Kataoka, Ian Rosenbaum, Chris Froh and Florian Conzetti. One can see from the photo below that to say they had their hands full would be a true understatement.

The concert’s impact was mesmerizing and powerful. Nothing in the festival could have made us prouder than the virtuosity and versatility of our incredible collection of performers that night, nor the sight of a packed audience on its feet screaming bravo’s at the conclusion of a truly adventurous program.

During the next main stage program, titled “Transitions”, we explored where music went in the wake of Dvořák’s Romantic age, seeking palpable connections between the music of the nineteenth century and modern times. Wu Han opened the program alone with Brahms’s late Intermezzi, Op. 118, which she described as the most intimate music of the festival, and also some of the most forward-looking of the late Romantic era.

Cellist Dmitri Atapine and pianist Hyeyeon Park then performed a selection of works by the Second Viennese School composer Anton Webern that perfectly documented the transition from the tonal to the atonal age. Webern’s first two pieces, composed in 1899, sound much like the Brahms that Wu Han had just finished, but his second set of three pieces, composed fifteen years later, are completely without key centers, and derive their hyper-romantic, expressionist emotion through both overt and suggestive musical gestures, as well as extreme dynamic levels. Our exceptional performers – both faculty of the Chamber Music Institute as well as graduates of the International Performers program – made the works truly their own, as they moved between all five pieces without a break, playing both cello and piano parts from memory. It was a highlight of the festival for me and Wu Han to watch another cello-piano duo take over such repertoire with expertise, dedication, and captivating charisma.

Also on the program was the Concertino by Dvořák’s musical descendant Leoš Janáček, a work that shows the colorful Czech folk idiom in full twentieth-century bloom.

The final concert in the festival’s Carte Blanche series was entrusted to the powerhouse pianist Gilles Vonsattel, who made his Music@Menlo debut last season in a blazing performance of the Franck Quintet. His program for this festival centered on the ideas of nationalism and revolution, two social phenomena that were strongly present throughout Europe during Dvořák’s lifetime. He began with two works by history’s greatest revolutionary composer, Beethoven, and both the sad stillness and bursting anger of Beethoven’s “Moonlight” Sonata were duly echoed in the work that followed, Liszt’s Funerailles. After an intermission during which all the pianists in the room said that they had better go practice, Gilles returned to perform one of the most beautiful pieces of Janáček that I have ever heard, his Sonata 1.X.1905 which mourns the death of a young Czech student, killed by pro-German forces while demonstrating for the building of Czech-speaking university. Saint-Saëns’s Africa followed, a wild, tour-de-force for the piano inspired by the composer’s trip to Egypt and Algeria. The recital concluded with Fredric Rzewski’s 1979 work titled Winnsboro Cotton Mill Blues, and inspired by the poem of an anonymous cotton mill worker describing the mill’s harsh conditions, written in 1880. Gilles’s phenomenal performance of this mind-twisting work, all from memory like the rest of his recital, left all of us cheering and shaking our heads in disbelief. From Beethoven’s sophisticated late Bagatelles to Rzewski’s pictorial, jazz-infused tone poem, Gilles had covered all the bases, basically hitting it out of the park.

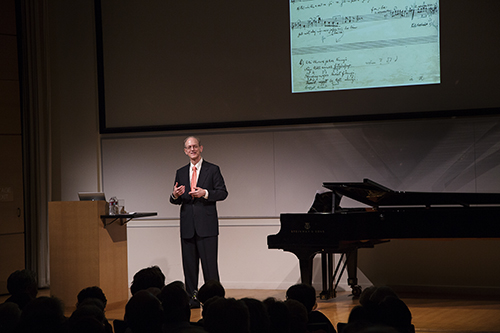

Along the way, Encounter Leader Michael Parloff returned for his third consecutive Music@Menlo appearance to enlighten us on late nineteenth and early twentieth century’s composers who delved into the folk music of their native lands. As usual, Michael came prepared with a veritable galaxy of images, recordings, videos and information, streamed together seamlessly, which added up to one of the finest lectures on music that we’ve heard anywhere.

We would have neglected a great opportunity had we not devoted an entire evening – our seventh concert program titled “Hungarica” – to the music of Dvořák’s great neighboring country, Hungary. In doing so, we proudly brought to the stage a spectacular collection of performers, some of them new to Menlo this season (cellist Narek Hakhnazaryan and violinists Nicolas Dautricourt and Alexander Sitkovetsky). Joining them were more recent additions to our main stage roster (violinist Benjamin Beilman and pianist Gloria Chien) as well as Music@Menlo veterans: violinist Jorja Fleezanis, violist Paul Neubauer, and, for good measure, Wu Han and me. The rather wild program included music by Liszt, Ligeti, Bartók, Kodály, and Dohnányi, all of it invigorating to play and hear.

Prior to our concluding performances, Encounter Leader Ara Guzelimian returned to confront a subject that few could with such passion and sensitivity: the persecution of musicians, artists, and art itself during the eras of Nazism and Communism. The story is no better illustrated than through the Czech lens, as the subjugation of Czechoslovakia by the Nazis meant not only the end of progressive Czech music, but also the negation of the country’s proud heritage, as we had heard about first-hand from William Lobkowicz, whose entire family was forced to flee their homeland twice during the 1930’s and 40’s.

Ara’s brilliantly planned and moving Encounter led us through the era with music composed in Terezín, or Theresienstadt in German, the “show camp” set up by the Nazis to try to convince the outside world that Jews were being humanely treated. Nothing could have been further from the truth, but the only positive outcome of this staged community was that it was necessary to produce art as a sign of social health, and therefore art was allowed and enabled to happen by the monstrously cruel people who ran it. The Encounter included a film clip of the late Alice Herz-Sommer, a pianist who survived Terezín and who performed one hundred and fifty concerts there. She passed away last spring in London at the age of 110, and at 109 she was still practicing the piano some three hours a day. The film made about her, called “The Lady in Number 6: Music Saved my Life” won the Oscar for Best Documentary the week after she died, and is now available to watch on Netflix and can be purchased directly from the producer. In addition, I should mention that our great friend and colleague Daniel Hope recently created and hosted a documentary on Terezín called “Refuge in Music” which has been released by Deutsche Grammophon. Both films are compelling and beautifully told accounts of this sad yet inspiring chapter of human history.

For our eighth and final concert program, “Bridging Dvořák”, we collected a sampling of the festival’s music and ideas, juxtaposing works that, we hoped, would truly summarize the idea of Around Dvořák. Beginning with a work by the acknowledged father of Czech music, Bedřich Smetana, we moved on to the delightful Serenade for string trio by the Hungarian Dohnányi. The centerpiece of this program, however, was undeniably the String Sextet by Erwin Schulhoff, one of the brightest lights of Czech music during the early part of the 20th century. This haunting work, which somehow presages the horrific events of World War II and Schulhoff’s own untimely death, provided our festival with its most powerful link from the colorful, mostly cheerful world that Dvořák knew, to the world of the twentieth century and the one we live in now, with ups and downs of proportions unimaginable during Dvořák’s age.

It would not have been fitting, however, to end such a joyous festival with music as disturbing as the Schulhoff, so we decided to send our listeners off with one of chamber music’s most beloved and often-heard works, Dvořák’s Piano Quintet in A Major. Joining us was pianist Anne-Marie McDermott, who headed a powerful ensemble that brought the audience to its feet, and Music@Menlo 2014 to a glowing conclusion.